Correspondence between Better Statistics CIC and Richard Heys, Deputy Chief Economist at the ONS

Correspondence between Better Statistics CIC and Richard Heys, Deputy Chief Economist at the ONS

From: Heys, Richard

Sent: 16 September 2021 17:49

To: Tony Dent

Tony,

Thank you for your feedback – this is very much a research piece aimed at generating discussion about how best to address a substantial issue: As the UN Secretary General’s recent vision document set out as one of its six themes: ‘now is the time to correct a glaring blind spot in how we measure economic prosperity and progress. When profits come at the expense of people and our planet, we are left with an incomplete picture of the true cost of economic growth. As currently measured, gross domestic product (GDP) fails to capture the human and environmental destruction of some business activities. I call for new measures to complement GDP, so that people can gain a full understanding of the impacts of business activities and how we can and must do better to support people and our planet.’

You raise a number of detailed points around the content of the paper, but in paragraph one you refer to the process of consulting on the SNA. I have taken the opportunity to reply to Paul on this to discuss potential options for how to engage a wider variety of stakeholders in discussion, as we are keen to find ways to work with Stats Users Net. You also raised an important issue around the communication of economic statistics which has developed a jargon and set of terms which are not readily accessible. There are numerous examples of this and it is a topic the international community is taking very seriously: there are four task-teams which have been launched, one of which is targeted at communications issues (the others are ‘globalisation’, ‘digitalisation’ and ‘well-being & sustainability’). Sanjiv Mahajan from the ONS is the chair for this task-team and would be well placed to join a discussion on this area of work. You also mention the need for the national accounts include negative aspects associated with, for example, degradation of the environment. I am pleased to confirm this topic is under discussion under the SNA task-teams, so this might happen in SNA 2025. Our work take the opportunity to explore the empirical importance of this factor to support the acceptance of this change.

Moving on to some of the detailed comments, which I appreciate, you flag the technical use of the term ‘welfare’. I’m going to admit we wrote this as an academic-style discussion paper, but we are always open to feedback. The key distinction we were trying to draw is between the existing suite of well-being measures, which compose a dashboard of different economic and social metrics and which we are not looking to substitute for, and economic welfare which covers a uniquely economic assessment of the value received by consumers from the full range of market and non-market interactions and transactions, whereas GDP covers strictly only market transactions and those non-market transactions which are suitably close (e.g. public sector). As you’ve noted from the paper, our interest is in developing metrics which can complement GDP and give a wider perspective. GDP’s strengths in terms of measuring the market economy are clear, but if we expect people to look beyond this measure when considering wider factors it is imperative to provide meaningful alternatives, and if possible allow us to disaggregate progress into that which is caused by increases in GDP and that which comes from elsewhere. As such, you are correct we look at this in an additive way: we don’t look to remove ‘bad expenditure’ from GDP (that is spending on cigarettes or drugs for example), but add other components in an effort to gain that fuller picture. However, you are correct there are alternatives and this is something we will consider as we move forward.

You flagged the need to be innovative in our use of data and ways of thinking. We completely agree with this, but we have limited resources, and are aware that other countries, particularly those in the developing world will struggle to fund multiple strands of statistics work. As such, we’ve focussed on doing what we can to not re-invent the wheel, but experiment in terms of how we could better utilise the data and frameworks our peers will be more likely to have access to. To be brutally honest, one of the key problems with many alternative metrics is they cannot be replicated in multiple countries who will never be able to afford to deliver multiple datasets against different frameworks. Aiming for the long-term, we therefore have used the widely agreed SNA and SEEA frameworks to enable eventual wider uptake. We have already seen some success on this point with Canada expressing an interest in replicating our approach. Also, one of the fundamental elements this retains is objective weighting through relative prices: we view this is fundamental to ensuring a viable metric.

I cannot agree more on the importance of capital – we very much accept the points you raised:

- The rate of return is wholly dependent on how much capital you view the return being spread over: if one recognises the contribution of land, natural capital, human capital and wider intangibles into production, a larger denominator would inevitably suggest the resulting calculation would deliver a smaller estimate. This is a recognised feature of our MFP estimates where endogenous rates of return appear high because some of the aforementioned factors of production are swept up in the MFP residual rather than included as capital inputs.

- Our work has revealed some of the challenges here, which is why we presently exclude wider natural capital measures, as you noted. This was a tactical rather than strategic decision at this point: we very much do wish to include these elements in the model. We did not for the following reasons: firstly the unavailability of capital consumption data to accompany investment flows, the existence of generally short time series, and the fact that those natural capital series outside of the national accounts are generally relatively small, so we decided there was greater merit in pushing forward.

- In relation to Intellectual Property Products, we consider their inclusion is merited for two reasons; firstly many IPPs were incorporated into SNA 2008, with others excluded because methods had not yet been developed, so for empirical rather than conceptual reasons. Given the world-leading work the UK has undertaken in this space, it would seem unusual to not recognise this continued momentum, in particular because our published estimates evidence that investment in these types of assets broadly equal investment in traditional tangible assets, reflecting the pace in change in the modern economy.

In terms of your question around what to do with this analysis, we see three conclusions of being of merit. Importantly, I would ask you to note that these findings are, like the research, the sole work of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the view of the ONS as an institution:

- Relating to the merit of including the flow of value produced by unpaid household services, we would argue its performance over recent years is a key feature of the analysis: Unpaid work ‘should’ rise relative to paid activity (i.e GDP) in a recession, and then decrease subsequently. The period after 2010 is, we think, notable in that the rewards from unpaid work as a share of all work remained sticky and did not fall back, indeed grew further, with outputs from unpaid work driving more than half of total growth over this period. In short, society saw a generational shift away from generating value from paid to generating value from unpaid activity. This may have some explanatory power towards the productivity puzzle if more productive staff decided they did not wish to return to work, but importantly we want to consider distributional information to really understand what happened here: At its core, it suggests (although we don’t yet have the analysis to prove this) a move in economic power from those earning paid income to those living off savings / pensions / other assets. We consider this an important question meriting further investigation.

- It also tells us something key about earnings, which is why we conceptualise this work in terms of income: the waged sector (GDP) has seen relatively weak growth compared to the overall growth in value from the unpaid sector – if one is reliant on a wage this suggests a relatively weak performance compared to someone who is not. Given that we know that hours worked amongst those with higher qualification has grown faster than those with lower qualifications (see recent productivity releases), and has, I believe, experienced faster wage growth, this research informs us that the distributional impact of unpaid work requires close analysis: if one is a grandparent retired on a substantial pension who enjoys taking the grandchildren to the beach / museum / park etc, this is rather different to the stereotypical single mother in a small flat who can’t find work which pays enough to purchase childcare.

- Finally, the other key story we drew from the data is the trajectory of atmosphere degradation over time. While a lot of caution should be given to the exact movements we see that, despite carbon emissions falling at an (internationally) relatively steep rate since roughly 2010, the level of atmosphere degradation (measured as a share of GDP) has remained fairly constant over time. The reason for this is that, as the climate has warmed, the damage associated with each unit of carbon emitted has increased, and this effect has counteracted the fall in emissions. While the model itself is fairly simply, being able to draw out a key interaction like this is incredibly helpful for understanding the impact climate change could be having on the economy.

Thank you for coming back with your comments – we really appreciate the time you’ve clearly taken to review our paper and pull your thoughts together. We are looking to update our paper as data becomes available and look forward to continuing this conversation.

Yours

R

Richard Heys| Deputy Chief Economist – Productivity, Research Partnerships and Professional Development

Office for National Statistics | Swyddfa Ystadegau Gwladol

Posting on SUN forum, 7th of September 2021, by Tony Dent:

Paul,

In respect of the recent posting on SUN of your email to Richard Heys, we at Better Statistics CIC (BSC) echo your concern that the ONS should engage various users in the process to revise our national accounts. However, our concerns extend beyond public engagement to consideration of the approach that Richard and others are taking to modernising the National Accounts, as described in his blog and the associated discussion paper.

Firstly, we are concerned that the language used by the ONS often fails to resonate with the more casual reader, for example the impression gained by the title of the blog “Building a Bridge from GDP to Welfare” is that the intention is to replace GDP with something entitled, or best described as, welfare. This seems insensitive to the fact that the term welfare is already in extensive use with a well understood, common-sense meaning (e.g. the welfare state). A meaning very different from that used by economists as suggested for the national accounts.

We at BSC have come to these issues only recently and we recognize that the ONS has used the term ‘welfare’ for quite a while, but we consider this use of the term to be confusing. Meanwhile we accept that ONS do not wish to use the term ‘wellbeing’ because they prefer to continue with objective measures to replace GDP, and the ONS has always associated wellbeing with one or more subjective measures. For our part we would have expected that ‘wellbeing’ as subjectively determined from population surveys, might be used as the determinant of the success of policies that could be associated with the ‘new’ GDP, but such a relationship does not appear to be anticipated by the full discussion paper GDP and Welfare: Empirical Estimates of a Spectrum of Opportunity where they say “When referring to “welfare” in this article, we are using it in this narrow sense – as “economic” welfare. We reserve “well-being” for a more expansive and general definition.”

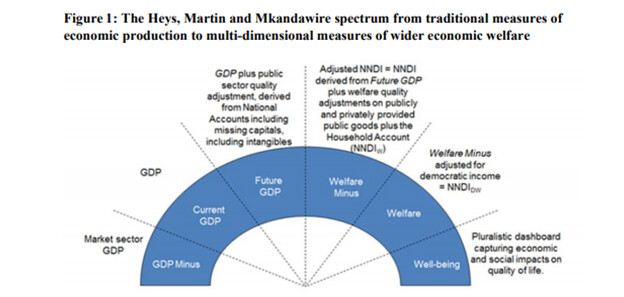

Moreover, the following diagram illustrates the relationship between welfare and wellbeing as seen by the authors:

We interpret this spectrum as indicating that as we move around the hemisphere more elements become included such that, for example, all the elements of the current GDP measurement would be included on the final wellbeing dashboard.

This interpretation is supported by Richard Heys’ blog, although there is a hint that it might not be appropriate to take it literally and that, perhaps some elements of current GDP as presently measured in the National accounts may not be considered appropriate for future use. Nevertheless we question the value of the four main aims that the ONS economists have stated they are seeking to achieve, as follows:

- “We want to use pre-existing data as much as possible”. Economists are always modeling the future based upon past experience, a process which can often lead to errors and is possibly less useful now than it has ever been. Far better that we should use only the necessary pre-existing data supplemented with new data as may be required to fill the full range of user needs.

- “We want to use existing International agreed frameworks and methodologies centred around national accounting methods as far as possible”. Once again, the ONS chooses to constrain its’ ideas by ensuring that we should avoid considering any revolutionary thought, as far as possible. Existing frameworks have not noticeably led to any improvement in dealing with the main priorities facing our society and many other societies since the last 2008 revision. In particular the problems created by the financial crash of 2008 resulting in stagnating incomes for most households and the increasing destruction of homes and livelihoods from global warming.

- “We want to reflect the wider range of factors which impact economic welfare by bringing unpaid household production and flows of benefit arising from the environment into the picture to reflect that increasingly we don’t only derive economic value from what we purchase and consume”. It is difficult to argue with this as suggestions for expanding the current measurement of the ‘real’ economy, although we might disagree with the way these factors are to be measured. We would, however, disagree with the assertion that the values associated with each of the stated elements are increasing. If, as is frequently suggested, the quality of the environment is deteriorating, would it not be implicit that the benefits derived from the environment are also decreasing?

- “We want to recognise the importance of capital, in all its forms”. We certainly could not disagree with a system that recognises the potential value of human capital and of the environment. However, we are concerned by the fact that one measure of economic success has been the return on capital employed. Historically that has been determined by how resources have been exploited to produce goods and services, whereas we assume that future success in respect of environmental capital will be determined not by exploitation but by preservation.

Necessarily the blog does not provide the methodological detail to understand how the ONS proposes to deal with the fourth item above. However, there are indications within the main discussion paper that, for the first time, the national accounts could include negative aspects associated with activities such as those responsible for the degradation of the atmosphere. At least that is the interpretation we place upon the following extract from the discussion paper:

“Under this method, the cost of the degradation is borne by the economic unit which caused the degradation. This method is useful where there are multiple contributors to degradation, and the effects of the degradation happen over a long timeframe – both of which are key features of atmosphere degradation due to climate change. Simply put, this presents the damage to the atmosphere caused by UK carbon emissions as being degradation in the UK’s accounts, regardless of who owns the atmosphere”.

This more revolutionary approach is missing from Mr. Heys’ blog and the full discussion paper confirms that the degradation of ‘mother nature’ other than that associated with the atmosphere is left for later consideration. Thus there is no reference to any reduction in ‘capital’ associated with loss of habitat or water pollution, whether rivers or coastal waters. Other elements on the list for future consideration by the ONS are Human Capital and free Digital Services and Platforms. Although we can accept that there is value to be derived from an agreed framework for the former, we would suggest that the latter is likely to be swiftly changing and not susceptible to value judgement in any meaningful way. Meanwhile we comment upon the following adjustments to GDP as considered in the discussion paper:

- Quality adjustment to non-market public services : BCS recognise that this adjustment has particular value for international GDP comparisons, where there can be significant differences between the boundaries of public and private services by country.

- Investment in additional Intellectual Property Products (IPPs, i.e. additional ‘intangible capitals’): BCS consider this extension to GDP as somewhat tenuous. Possibly we do not understand the proposed procedures, for example what value is given to ‘on the job training’? The suggestion also seems to be that companies can value ‘brands’ on their balance sheet as a result of ‘internal’ work such as social media engagement. Such ideas were considered to be highly controversial in the 1980’s. BCS are aware of an ESCoE paper on this subject in the May conference but not of any subsequent follow up.

- The flow of benefits / income received from natural capitals : this adjustment seems not to have been covered within the paper other than the degradation of the atmosphere as mentioned above.

- The flow of benefits / shadow income from services produced by the household for own-use : the paper provides a detailed description of the process used to include this ‘household production’ into the national accounts. Moreover, it seems that its inclusion increases GDP by more than 5%. But it is, surely, irrelevant to the wider scheme of things to claim that someone who paints their own front room has provided (received?) a ‘shadow income’.

Richard Heys has said “what we measure affects what we do”, but we really are unsure as to what we would do as a result of changes in some of the above measurements. It seems to us to be more important to ensure that we should measure the effects of what we do and that we should always consider what the objective is of any proposed action and therefore how we should measure the effect.

So, the question is “what is the objective behind the discussion paper and therefore the blog”? If, as is suggested by the introduction, it is to create a system which can more readily respond to changes, whether technological or environmental, then we need something much simpler than that described in the discussion paper.

It seems that none of today’s statisticians or economists have any sympathy for Occam’s razor. Instead, they persist in increasing the complexity of their work so that it becomes less and less accessible to ordinary people. We need to do better than this if people are to understand and agree with the processes suggested for ‘levelling up’. That seems to be a straightforward concept in many people’s minds and should have a relatively straightforward way to measure success.

As background, BSC are also in the process of reviewing the Legatum institute’s Prosperity Index as a better statistic in respect of its potential contribution to the government’s levelling up agenda. We hope to publish our review after the Legatum Institute has had the opportunity to comment on it. However, we also believe the Index to be an unhelpfully complex measure, a factor that makes it less accessible than it could be to many potential users.

We conclude that the ONS must try harder to communicate their work and that public engagement will help the process and not hinder it. We also suggest that, because of the continuing importance of GDP to the National Accounts, it should be continued as at present but that one or more new measures should be added in our National Statistics to clarify the ‘key performance indicators’ now required to demonstrate progress with today’s concerns. We believe that such an approach could assist with the levelling up agenda and would show more respect for the value of Occam’s razor in the development of new statistics.

We hope that these observations will encourage others to engage with this very important topic.

With all good wishes,

Tony Dent, Director Better Statistics CIC